In Chinese there is an old word for landscape, composed of two root characters: shan (mountains) and shui (water). For the last thirty-some years I have been gardening, meditating, and teaching in both a mountain and a water landscape on the edge of the San Andreas Fault line in the Bay Area of northern California.

I lived for much of that time at Green Gulch Farm, a Zen Buddhist meditation and retreat center with a working organic farm and garden. Green Gulch Farm is located on the western margin of North America, about a half-hour’s drive north of San Francisco, at Muir Beach in Marin County. Now I live nearby, still in the deep bottomland of Muir Beach on that delicate seamline where solid earth floats, buckling and shifting without notice.

Green Gulch Valley is a very old place. The soil was formed under the Pacific Ocean, the deepest and largest ocean in the world, which now breaks at its edge. Green Gulch soil is really compressed ocean bottom, heaved up millennia ago to become dry land. Made of the intensely folded and faulted rocks of the Franciscan complex, this bottomland soil includes Mesozoic marine sandstone and shale, chert, seafloor volcanic rock, and rare metamorphic rock interlaced with compressed marine fossils. When I look deeply I see that we are growing lettuce on the bottom of the ocean.Mount Tamalpais, the sacred mountain of the native Ohlone tribes of the Bay Area, rises abruptly from the steep ocean cliffs at Muir Beach, climbing two thousand five hundred feet to its summit. Diaz Ridge, the foot ridge of Mount Tamalpais, defines the northwestern boundary of Green Gulch Farm, while Coyote Ridge, another part of the Coast Ranges, marks the southeastern margin of our watershed. In between these craggy coastal mountains, the green dragon snakes out to the sea.

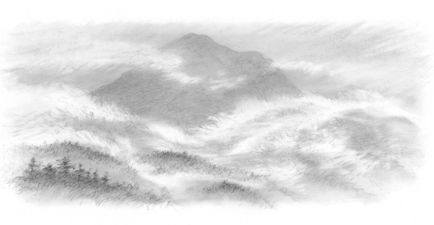

Brush and ink paintings of Chinese landscapes show endless misty mountains molded by running water, or still lakes reflecting raggedly clouded peaks. These landscapes are never solid, never static. Always in motion, they move just below the rolling fog. The great thirteenth-century Zen master Eihei Dogen writes in his “Mountains and Rivers Sutra” that the green mountains are always walking and that they travel on water as well as across land. The mountains and rivers of this time and place are also never only what they seem to be.

I first read the “Mountains and Rivers Sutra” in 1975 at Tassajara Zen Mountain Center. Tassajara is a seasonal monastery and retreat center in the Ventana Wilderness of the Los Padres National Forest that, like Green Gulch Farm, is a branch of the San Francisco Zen Center. I copied the sutra out by hand and still reread it every year. “Although mountains belong to the nation,” wrote Dogen, “mountains belong to people who love them.” Gardeners are mountain-and-river pilgrims. We commit ourselves to the landscapes we know and love, traveling over their jagged terrain step by step. When I slow down and read the “Mountains and Rivers Sutra” carefully, or when I step up close to a Chinese scroll, I always find a tiny human figure tucked between the folded canyons of the green mountains, meandering with the aid of a crooked pilgrim’s staff through the shallow backwaters of rivers without end.

I first read the “Mountains and Rivers Sutra” in 1975 at Tassajara Zen Mountain Center. Tassajara is a seasonal monastery and retreat center in the Ventana Wilderness of the Los Padres National Forest that, like Green Gulch Farm, is a branch of the San Francisco Zen Center. I copied the sutra out by hand and still reread it every year. “Although mountains belong to the nation,” wrote Dogen, “mountains belong to people who love them.” Gardeners are mountain-and-river pilgrims. We commit ourselves to the landscapes we know and love, traveling over their jagged terrain step by step. When I slow down and read the “Mountains and Rivers Sutra” carefully, or when I step up close to a Chinese scroll, I always find a tiny human figure tucked between the folded canyons of the green mountains, meandering with the aid of a crooked pilgrim’s staff through the shallow backwaters of rivers without end.

The first time I saw Green Gulch Farm I was on foot, and feeling like that tiny pilgrim lost in a Chinese landscape painting. When Peter Rudnick, not yet my husband, and I decided to leave the mountain wilderness of Tassajara in the autumn of 1975 to help San Francisco Zen Center establish a small organic farm at the edge of the Pacific Ocean, we decided to make the pilgrimage to Green Gulch on foot.

I had been working in the garden at Tassajara and I did not want to leave, but Peter was eager for the move. He loved change. So, in high spirits, he led our hike out, while I dragged along like a reluctant exile. The Tassajara tomatoes were just coming into color, and I was walking out. The dark opal Japanese eggplants were finally growing plump and ready to harvest, and I was walking out. The work positions at a Zen monastery are rotated every year, which is supposed to keep Zen students from becoming attached to one job or one identity. But it was too late for me, far too late. I had already dedicated countless hours of precious Zen meditation to plotting the layout of the Tassajara garden: ‘Touchon’ carrots sowed in early April in the lower garden would follow the winter crop of Chinese cabbage. By late July the carrots would be pulled and followed by a sowing of rhubarb chard for next autumn’s kitchen. A blood sample taken from any part of my body would have confirmed the bitter truth: I carried in every corpuscle the incurable obsession of gardening.

It took us three full days to walk out of the wild and geologically young mountains, the age of the Himalayas and just about as sheer. Eventually I picked up my pace, the call of the coast pulling me now through the Ventana Wilderness. It was almost dark on the third day when Peter and I finally pushed out of the chaparral underbrush into the dark redwood canyons of the coast above the Big Sur River. We smelled of the loneliness of walking for hours on unmarked trails. Woodsmoke from our nightly fires filled our hair. I was repeating lines from the “Mountains and Rivers Sutra” to myself as we walked, as a magical incantation so that I would never forget Tassajara. “If you doubt mountains walking, you do not know your own walking; it is not that you do not walk, but that you do not know or understand your own walking . . . at this moment, do not doubt the green mountains’ walking.”

I remember the cool winds coming up from the redwoods of the Sur River canyon as we headed northwest to the coast. We heard the thick blood of the river pumping through the granite veins of the canyon. Far in the distance white shorebirds circled in slow hypnotic gyres below us, calling and sailing on the updrafts, the ocean a scant five miles away. It was almost dark by the time we finished our descent to the river canyon. We made a fire of broken redwood branches and oak leaf duff and cooked the last of our carrots and potatoes into a stew. We had a little hard bread left over and a heel of leathery Parmesan cheese. We ate without speaking, too tired to talk. I lay down and watched the stars appear at the top of the ancient redwoods. Peter rolled out our sleeping bags while I tracked the appearance of the North Star in the dome of the night.

In the closing hours of the night, when the coals of the stars were banked in the soft gray ash of dawn, we were wakened by the thunderous sound of a redwood tree falling in a steep side canyon of the river. We heard the tree creak and break, fifteen or sixteen loud reports like cannon fire, and then the long downward surge of the falling giant. The sound went on forever as the tree crashed down through other redwoods and finally fell on the thick duff litter of the forest floor.